As the lead nurse in charge of the PMTCT (prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission) clinic at Mchinji Health Center in western Malawi, Kennedy Munthali has a packed schedule—overseeing the care of about 700 women who are either pregnant or are nursing infants, in a typical month.

The PMTCT program has been a key factor of the dramatic decline in HIV incidence over the past 20 years in this southern African nation. The program oversees HIV testing and treatment, prenatal care, delivery services, and postnatal care—along with TB testing and treatment and family planning services.

Until 2019, the Mchinji Health Center relied on a paper folder system to track PMTCT clients and record details of their care and vital health information about their children. Maintaining this system burned vital clinic hours and made follow-up more difficult, requiring that health workers comb through folders to identify patients who had missed appointments or required a check-in.

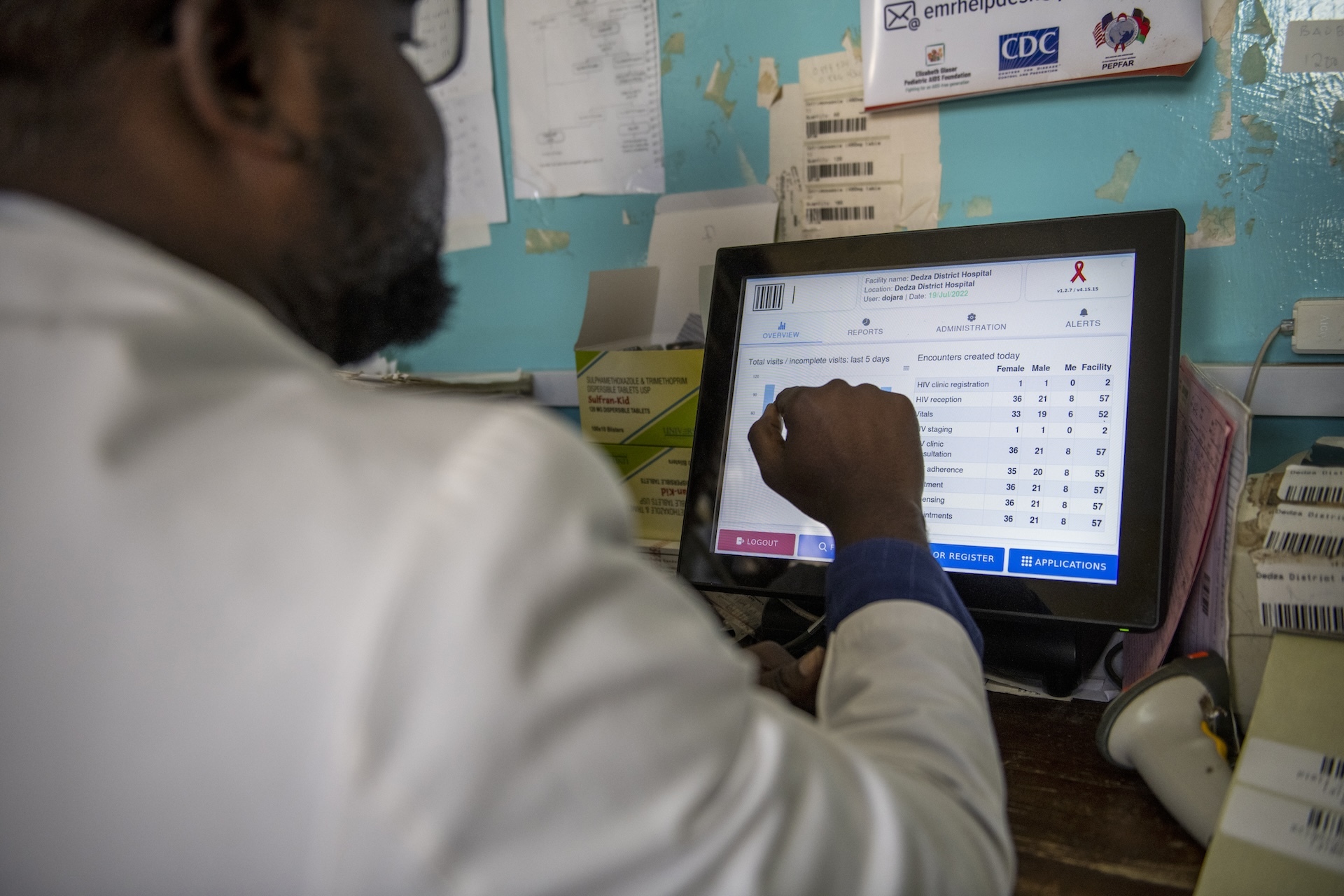

But now the clinic uses an electronic medical record system that clinicians log into at the point of care to record medical information.

Thanks to a modern health information system (HIS), Nurse Munthali’s staff has more time to spend with patients, and the health records are more accurate and up to date. The health information system includes an electronic medical record system (EMRS) connected to a lab information management system (LIMS) allowing health workers to generate clinic reports or check on a patient with a few clicks of the mouse.

“It’s a busy clinic,” says Munthali, “so these reports, they help us a lot. We are able to see the areas which we are not doing well.

We can generate a missed appointment report on a daily basis. It [also] means that if a patient wants to move from this facility and start service at a different location, we can print out the particulars so that we transfer this patient, and they continue care.”

Munthali is able to spend more time with patients, return results back to them quickly, and monitor their overall health more effectively through the new system. Additionally, a stride forward with the National ID Registry holds promise for better health tracking throughout an individual’s life.

From Paper to Screens

Electronic medical records were introduced in Malawi in 2005 by Baobab Health at Kamuzu Central Hospital in the capital city of Lilongwe.

“The main purpose of it was just to develop a system that would support that hospital for automation of processes,” says Charlie Maere, the Global Digital Health and Data Analytics director at EGPAF. “CDC and PEPFAR took interest on that system and asked if we could tailor this to the national HIV program.”

“The hospitals were islands at that time,” says Maere. “We started building infrastructure so that we could exchange data across facilities. The main problem was capturing data so that people make sense of the data and then use the data for decision making.”

“We previously only had a health passport for patients,” says Veena Sampathkumar, vice president of EGPAF Program Implementation and Country Management. “It’s literally a small booklet held by the client that might have just a summary of the diagnosis and the treatment. You don’t get a full perspective of that particular individual.”

During a clinic visit, the clinician would record information in the booklet and copy it onto a paper record called a mastercard, which was then filed in a huge filing system at the clinic.

“But somebody living with HIV who’s been in care for 10 or 15 years, might have different health experiences across time that might not be fully captured on the paper record,” explains Sampathkumar.

“Electronic systems make it easier for clinicians to access information about the patient in front of them—whether they go to multiple facilities or are at the same facility but in a different department,” she says. “Nurses are able to have a 360-degree perspective of the patient and are able to tailor care to their specific needs at that moment in time.”

The old system was time consuming for health workers tracking patients. Efrida Ghodede, EGPAF-Malawi’s HIS implementation lead, recalls a health facility that she visited as she was building the electronic medical record system for Malawi.

“We found them flipping over heaps of files. And I asked them, ‘What are you doing?’ They said, ‘We don’t know who’s coming tomorrow. We’re just checking.'” Ghodede says that they spent three hours going through the folders.

The old system required sifting through stacks of papers to get the information needed.

Today, the electronic system is giving clinicians a 360-degree perspective.

Paper records are not only a burden at the site level; they also make it difficult to track national trends and identify gaps in the health system.

In Malawi’s recent past, in order to maintain statistics that showed the national incidence of HIV and details about testing, treatment, and so on, health officers had to be dispatched to sites around the country to copy data from paper registries and bring those numbers back to the central office of the Ministry of Health in Lilongwe. It was time consuming and prone to errors—despite the best efforts.

To launch the electronic medical record system, EGPAF program officers fanned out across Malawi over a period of several years to visit all 770 health facilities multiple times and assiduously transfer information from the paper mastercards. This was an adventure that required many bumpy rides across dirt roads and crossing rivers by canoe.

The very transfer process illustrated the inherent drawbacks to the paper system.

“There were gaps in the manual systems that missed vital information,” says Ghodede “Sometimes, handwriting was not very visible. We had torn registers, and some registers were missing. We had floods in Chewa and Nsanji and other places where all the registers were lost.”

A System and an Experience

When the first electronic medical record system in Malawi was pioneered in 2005, many facilities lacked computers.

“And there weren’t any smartphones or tablets,” says Martin Baki Suleman, senior software developer. “To assume that people would easily get into the habit of using a system where they’re using the computer would be quite tricky.”

Since those days, of course, smartphones have proliferated, and everyone is fairly adept at the features on their handheld device.

“We made a design consideration to use a touchscreen interface,” says Suleman. “And more than that, a point-of-sale type interface.”

Suleman says that this system is built on an open platform that can easily be adapted to other countries, giving Cameroon as a recent example.

“It was a pretty easy; implementation,” says Suleman, “because workflows are very similar in all countries. So it was basically just using the same interfaces from Malawi and updating and translating.”

EGPAF distributed electronic tablets, laptops, and desktop computers across facilities to meet varying needs. For example, a desktop computer might be more useful in a lab, while a tablet might be more useful in a clinician’s hands.

“This system is not designed merely for data collection. It’s built for a better clinic experience,” said Maere.

Maere gives the example of Starbucks. At the point of service in such a coffee shop, the person taking the order uses a touch screen, with prompts throughout the process to capture the customer’s specific requirements and information. Then that order is routed to the proper individual to fulfill the order, also using a touch screen to identify the information and to close the loop.

Each client is identified through a barcode, which makes them easier to track while keeping their records private. It also helps manage the queue at the facility so that everyone is not lining up in one place to get served.

Training health workers to use the new system was fairly straightforward.

“We don’t necessarily need anyone who’s ever used a computer before but intuitively just show them, Touch here, touch here,” says Suleman. “There’s one question per page, and it flows from page to page. So, as a clinician, it’s mostly you having a conversation with the client and basically just focusing on one question at a time. You reduce amount of typing. There’s no clicking with a mouse. It actually makes your life a bit quite easier.”

“You have the actual clinician with the patient collecting real-time data as opposed to the clinician writing down all that information and handing it over to a data clerk to be entered into the record. We end up winning in terms of the accuracy of data, and we save time and money,” says Suleman.

Nurse Munthali says that the automated prompts of the electronic system have been a game-changer.

“This new system saves lives,” says Munthali.

“Patients are more likely to keep taking their medications if clinic staff is tracking them. We are able to take care of patients without missing important information. And when they’re healthy, they’re able to live a happy, normal family life.”

“When a pregnant woman tests positive for HIV, she is immediately put on antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, which lowers her viral load so that she does not transmit HIV to her child in utero or during breastfeeding. That mother must remain on treatment through this entire period and the child must be tested periodically to ensure that the child is HIV-free.

“On the other hand, if a mother misses her clinic appointments and lapses in ARV adherence because the health worker was not alerted, that child is at risk of acquiring HIV and falling through the cracks, maybe even perishing.”

People at the Center

Data management conjures the image of impersonal technology, but in the case of Malawi’s health information system, people are very much the central focus.

“Children have very specific needs,” says Sampathkumar. “The health information system helps us tailor care to specific population groups, whether it’s a child in front of you, an adolescent, somebody who has recently recovered from TB—you’re able to tailor the care to that specific group as well as that particular individual’s need.”

“We can also call it people-centered because it supports the care providing team with opportunities to streamline their processes and procedures to actually focus on the quality of care rather than a lot more of administrative tasks.”

“Democratizing data” is how Maere refers to the health information system.

“It is basically allowing the creators of the data to make decisions,” says Maere.

“Democratizing data is making sure that as the data is being collected directly from patients, we can then share that data back to clinicians so that they can make decisions.”

“So if I am an ART nurse, I should be able to open up my system to see how many people I am expecting today. ‘Do I have enough drugs and supplies to make sure I can meet the needs of all these individuals?’”

“Ultimately, I see this as a tool and a solution to get us to an AIDS-free generation.”

Veena Sampathkumar VP Program Implementation and Country Management