“As employees of this health center, we consistently confront the difficulty of dealing with our emotions…These emotions inevitably accompany us to the office, and interacting with patients becomes our outlet for processing these feelings,” Neema Mpaki, healthcare worker from Tanzania.

While there are no shortages of systemic challenges when it comes to providing quality healthcare in Tanzania, provider empathy is a key ingredient that can be missing from the patient-provider relationship, particularly in interactions with young people and adolescents.

While there are no shortages of systemic challenges when it comes to providing quality healthcare in Tanzania, provider empathy is a key ingredient that can be missing from the patient-provider relationship, particularly in interactions with young people and adolescents.

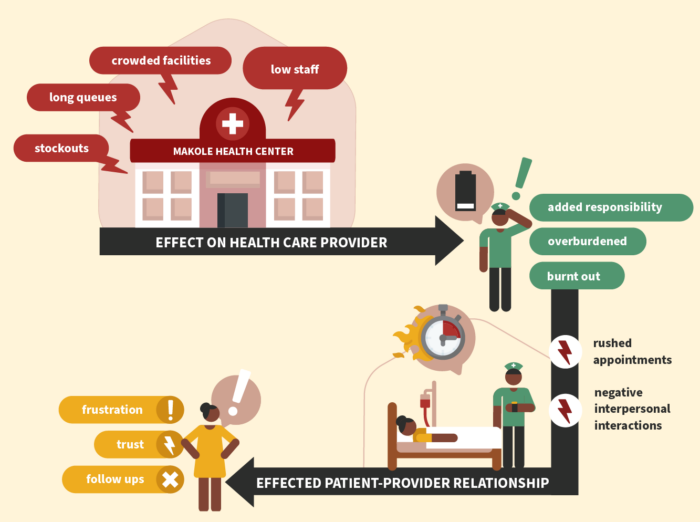

At the Makole Health Center in Dodoma, the challenges of stock-outs, long queues, and crowded facilities are a daily reality; this coupled with low staff retention rates perpetuates cycles of additional responsibility and burden of work falling on providers who are often burnt out and overburdened at baseline.

The knock-on effects of rushed appointments, and negative interpersonal interactions inevitably bleed into the patient-provider relationship, leaving fractures in trust, perpetual frustrations and loss of follow up in its wake.

A Human Solution

Recognizing this challenge, the USAID Afya Yangu Northern Project used human centered design (HCD) and undertook an in-depth co-creation process with various audiences; providers themselves, as well as adolescent boys and girls to better understand their varying perspectives on the foundational causes that strain interpersonal care and importantly, how to improve it.

Honoratha Mpaki, a 45-year-old health care provider, has had a profound sense of compassion and a desire to make a positive impact on the lives of others for as long as she can remember. This, coupled with a pivotal experience where she witnessed the critical role of health providers, solidified her desire to become one herself.

“I was inspired by the way healthcare providers, especially women like me, deliver services when I visit the hospital,” said Honoratha. “I admired and was fascinated by them. One day, I had the opportunity to talk to a healthcare provider, and I asked her what led her to be in this profession. She told me that it was through studying and pursuing her dreams diligently. This is the reason why I am a healthcare provider today.”

Honoratha has been providing HIV counseling and services to adolescents and youth over the last 21 years, alongside her colleague Neema Msemo. Like Honoratha, Neema was also inspired to become a healthcare provider from a young age. With a family legacy of compassion and service, Neemaʼs journey into the healthcare profession was largely influenced by her mother, a dedicated healthcare provider whom Neema admired for her empathy and respect in the provision of care. Over the last 7 years, Neema has been working alongside Honoratha, each providing healthcare to the best of their ability, despite personal challenges that come with being human and persistent systemic challenges that make the job more difficult.

“As employees of this health center, we consistently confront the difficulty of dealing with our emotions,” said Neema.

“There are instances when you depart from home after a disagreement with your spouse or encounter someone who upsets you directly during your commute. One day, as I was en route to the hospital, a text from my husband about dinner plans buzzed on my phone. The fatigue from the day ahead and the lingering irritation from the train argument converged, leading to a disagreement over something trivial. Words were exchanged, and the atmosphere became tense. These emotions inevitably accompany us to the office, and interacting with patients becomes our outlet for processing these feelings.”

This poses the question, HOW DO WE CARE FOR PROVIDERS WHO ARE PROVIDING CARE?

Finding Our Feelings

The USAID Afya Yangu Northern HCD Component undertook immersion interviews in hopes of inching closer to illuminating potential solutions from the point of view of stakeholders closest to the problem. Adolescent girls and boys from the community, as well as healthcare providers in the Makole Health Center, were asked to participate in immersion interviews. These interviews probed their perspectives, beliefs, experiences, and importantly, feelings on current patient-provider care, as well as desires and visions for what more empathetic care in the future might look like.

These immersions, coupled with a co-creation process, resulted in an emotional regulation prototype called Hisia Zetu or “Our Feelings”.

The aim of the poster is to re-emphasize that while systemic challenges may be out of providers control, emotional regulation is not. Intentionally hung by key transit areas within the clinic, the poster is laid out in a user-friendly way, guiding the healthcare provider through recognition and identification of feelings, as well as coping mechanisms to choose from. The feelings poster reminds and encourages healthcare providers to recognize their emotions and consider how to deal with them. Each emotion is accompanied by a realistic and feasible coping mechanism, conducive to the work environment and beyond.

The aim of the poster is to re-emphasize that while systemic challenges may be out of providers control, emotional regulation is not. Intentionally hung by key transit areas within the clinic, the poster is laid out in a user-friendly way, guiding the healthcare provider through recognition and identification of feelings, as well as coping mechanisms to choose from. The feelings poster reminds and encourages healthcare providers to recognize their emotions and consider how to deal with them. Each emotion is accompanied by a realistic and feasible coping mechanism, conducive to the work environment and beyond.

Knowing that the healthcare providers are always on the go, the HCD team created digital image versions of the poster that can be kept on a phone for ease of reference no matter where a healthcare provider is.

Feedback on Hisia Zetu has been inspiring and positive; healthcare providers like Honoratha and Neema have noted the improvements in interpersonal relationships amongst healthcare providers and clients alike.

“When I used the feeling poster, I felt relieved because I found a cure that can help to manage my feeling, and after I finish using the feeling poster, [Iʼve recognized my feelings] and I feel like the feeling has already disappeared in my head and Iʼm fine,” said Honoratha.

The feelings poster has facilitated opportunities for providers to not only discuss the content of the poster, but to also do so in more vulnerable and personal ways. This has created an environment where reflecting on oneʼs feelings, emotions, and experiences are more normalized, and as such, deeper and more meaningful interpersonal relationships are forged.

“As a nurse, I find it easy to navigate my emotions, and the emotion chart is a valuable tool,” said Neema.

“When experiencing anger or fatigue, I know the steps to take in order to regain balance and provide optimal care for my patients. It proves to be genuinely beneficial, It’s not just about being a nurse; it’s about being a holistic caregiver who understands the intricate dance of emotions and can navigate them skillfully for the well-being of both myself and those under my care.”

Emotional Intelligence in Action

Through improved provider emotional intelligence, there have been improvements to the patient-provider relationship: providers are more aware of and focused on addressing the emotional needs of youth, improving levels of empathy, and by extension, improving youths’ feelings of being understood and their overall healthcare experiences. Posters have also created opportunities for youth to be more engaged in their own care, evident through youth inquiries about Hisia Zetuʼs content and how it can be used in their own lives. By healthcare providers being more attuned to their emotions, and also those of their patients, the Makole Health Center is believed to have seen increased youth engagement as a result.

Hisia Zetu has brought about personal change for Neema and Honoratha. Their newfound awareness of emotional intelligence has enabled them to navigate challenges more effectively.

Honoratha reflects on the broader influence of the project, saying, “The project has helped us a lot, I can’t express enough gratitude.”

Collectively, the feelings posters have improved interpersonal relationships and have fostered a more supportive atmosphere for patients and providers alike. The USAID Afya Yangu Northern Project’s Hisia Zetu poster has shown the power in ʻtaking careʼ of providers who provide care. By understanding the challenge through the perspectives of those closest to the problem, this is a feasible and viable way to overcome the gap in empathy between provider and patient and we believe will lead to more empathetic and effective healthcare delivery.

The USAID Afya Yangu Northern is designed around client-centered approaches to address gaps in HIV, TB and family planning service delivery, while continuously building and transferring the capacity of local stakeholders for sustainable and country-led ownership.

USAID Afya Yangu Northern focuses intensely on direct service delivery across all regions in early project years, ensuring that gaps to epidemic control are identified, and tailored solutions are designed to meet the needs of vulnerable populations.