“My career journey into public health was influenced by my father,” says Sajida Julius Kimambo, M.D., M.P.H, the country director for the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric in Tanzania. “My father, Julius Kimambo, was a medical doctor in the Army. He died in 1986, when I was 12 years old. In many African cultures and settings, women don’t inherit anything, but I received a stethoscope from my dad. Growing up, I kept looking at that tool. I wanted to know what that tool was for.

“My career journey into public health was influenced by my father,” says Sajida Julius Kimambo, M.D., M.P.H, the country director for the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric in Tanzania. “My father, Julius Kimambo, was a medical doctor in the Army. He died in 1986, when I was 12 years old. In many African cultures and settings, women don’t inherit anything, but I received a stethoscope from my dad. Growing up, I kept looking at that tool. I wanted to know what that tool was for.

“With my father gone my mother, Maimuna Rwabyo, encouraged me to study hard, and she guided me to move into medicine,” says Dr. Kimambo. “She provided protection and encouragement so that I could eventually attend Muhimbili University Medical School.

“After I entered med school and saw firsthand the contribution of health care workers in saving lives, my motivation and passion continued to grow. I was so happy the first time I delivered a baby. The first cry of that baby was my most pleasing moment, which I will never forget. I continued to support women in labor, delivering babies, supporting them to their last push.”

But health care is not just about happy moments. During her upbringing and education, young Sajida was acutely aware of the public health crisis around her. HIV was burning through the population of Tanzania, and there was no effective treatment. By the end of the 1990s, more than 8% of people between the ages of 15 and 49 were living with HIV.

“I grew up when the stigma for HIV was very high,” says Dr. Kimambo. “When I was in medical school, I witnessed how difficult it was for people to care for HIV-infected family members due to stigma and poverty. I witnessed my own family contributing money monthly for a family member who was on antiretroviral treatment [ART] before the meds become publicly available through PEPFAR [the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief].

Women and HIV

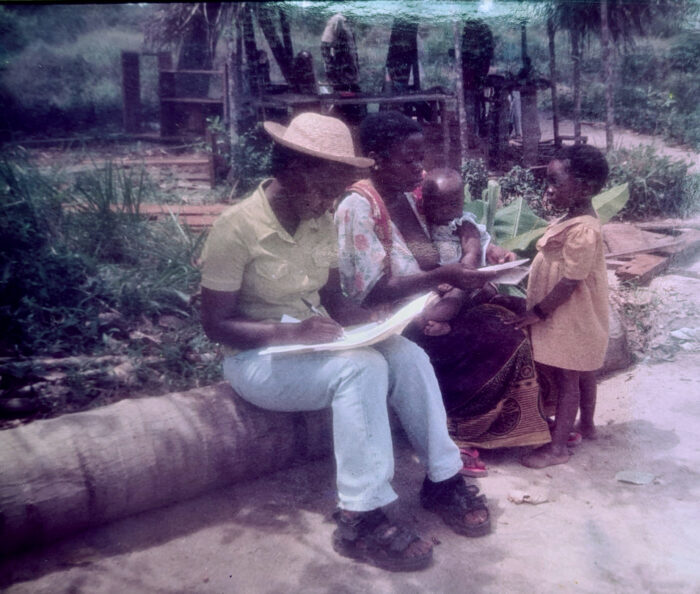

After graduating from medical school in 2002, Dr. Kimambo and her future husband, Dr. Johnson John Lyimo, were recruited to join the HIV Research Clinic—a collaboration between Muhimbili and Dartmouth Universities—where she worked on TB clinical trials and witnessed firsthand how HIV disproportionately affects women. (TB is the leading cause of death for people living with HIV.)

After graduating from medical school in 2002, Dr. Kimambo and her future husband, Dr. Johnson John Lyimo, were recruited to join the HIV Research Clinic—a collaboration between Muhimbili and Dartmouth Universities—where she worked on TB clinical trials and witnessed firsthand how HIV disproportionately affects women. (TB is the leading cause of death for people living with HIV.)

“The biological nature of women increases their risks for HIV acquisition, and other structural factors predispose women to acquire HIV infection more than men,” says Dr. Kimambo. “Most of our study cohort were women, and most had not disclosed their HIV status due to fear of gender-based violence and poverty.

“I recall interviewing an HIV-positive client at the clinic for baseline data. She mentioned of one of my uncles was her spouse. I was shocked when she said that she will not disclose her HIV status to him for fear of separation. Despite my shock, I composed myself and encouraged her to disclose her status. Unfortunately, she did not; they have both passed since then, due to AIDS-related illnesses. I only wish stigma had not kept them from disclosing, as maybe they could have sought treatment and still been with us today.”

“I got to understand what it was like to live with HIV in the early 2000s—when stigma, poverty, lack of meds, and emotional distress were outstanding,” says Dr. Kimambo. “I empathized with men and women living with HIV. I developed a network of HIV-positive friends; their families become my friends. My husband and I have continued to advocate for HIV clients since then.”

A Shift to Public Health

In her clinical practice, Dr. Kimambo saw the intersection of human rights and public health. Even if medical interventions are available, it means little to those who cannot access them.

“I witnessed children dying because of lack of blood, lack of medication, and so forth,” says Dr. Kimambo. “Imagine if you’re coming from a poor rural area, where you have to pay for medication, you have to pay for investigation, but you cannot. One time, I admitted a child, and she died in front of me because there was no blood in the blood bank. I approached her relatives to get some blood, but they were emaciated. They didn’t have any blood to donate.

“That night, I didn’t sleep,” says Dr. Kimambo. “So I shifted my career goals to public health. I decided to go on the prevention side—to prevent people from becoming sick.”

Dr. Kimambo enrolled in the Dartmouth School of Medicine, where she earned a Master’s of Public Health (MPH) degree in 2007. Then she went to work with the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Tanzania to support the scale-up of pediatric programs around HIV and TB, followed by work with UNICEF on HIV-related concerns for adolescents. While Dr. Kimambo was deeply passionate about her work crafting national policies and guidelines, she discovered that wanted to have greater role in implementing them.

Elizabeth Glaser’s Love

“I felt that I was missing something,” says Dr. Kimambo. “As I woman, a mother, and a girl growing up in a mix of urban and rural settings, I had witnessed firsthand the barriers for sustained health services to women and their families. So when I saw an opportunity to lead EGPAF in Tanzania, I said, Oh my God, I need to join these guys. I had first interacted with EGPAF when working with the CDC, and I had been moved by their holistic focus on children and mothers. I felt that that could be a great opportunity for quicker wins, quicker results with the policies that we were making at the national level.

As I woman, a mother, and a girl growing up, I had witnessed firsthand the barriers for sustained health services to women and their families. So when I saw an opportunity to lead EGPAF in Tanzania, I said, I need to join these guys. Dr. Sajida Julius Kimambo

“Of course, I came to learn about Elizabeth Glaser, and it increased my passion to continue to serve,” says Dr. Kimambo. “You can see the love that was spread by our founder, Elizabeth—how lives have been transformed—here in Tanzania, but also globally—through a mother’s love. The seed that she planted has saved countless women, children, and families.”

“Here in Tanzania, EGPAF has contributed to guideline development and improved health facility infrastructures and lab systems” says Dr. Kimambo. “We have supported thousands of beneficiaries in the PMTCT, ART, family planning, and TB services. In recent years, we have extended our arms to work with partners on programs to support early childhood development and orphans and vulnerable children.

Dr. Kimambo still has her father’s stethoscope. She hopes to pass it along to her grandchildren. “It’s still alive,” she comments, “even if it is no longer working.” Dr. Kimambo looks back in gratitude to a father and a mother who believed that she could help heal the world, and she hopes to see more faces like hers at the forefront of public health: “Competent Black and brown women need to be promoted in greater numbers to leadership positions at the global level,” she says.

And Dr, Kimambo looks forward to the day when Tanzania and all nations have forever eradicated the fear that a child might die from AIDS.

“Nelson Mandela used to say, ‘It always seems impossible until it’s done,’” says Dr. Kimambo. “We are continuing to work with our partners to ensure that we reach an AIDS-free generation. It is possible.”