As we mark World TB Day, the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF)’s Sr. Director, Innovation and New Technology, Cassandra Kelly Cirino, and Senior Program Officer at the African Union, Dr. Sheila Tamara Shawa, PhD engage in a Q&A session, sharing their expert insights and critical perspectives on the global state of childhood TB. Together, they explore innovative ways that the global health community can rally behind the creation of a TB-free future by reaching the population most at risk for TB infection: children.

Cassandra Kelly Cirino

Q: Why does an organization that focuses on pediatric HIV and AIDS take such a strong role in addressing pediatric TB?

Q: Why does an organization that focuses on pediatric HIV and AIDS take such a strong role in addressing pediatric TB?

A: To address pediatric HIV, it’s impossible to ignore TB. Children who are HIV-positive are at extreme risk of contracting and dying from TB. In order to treat children for HIV, we need to support their comprehensive health, and this includes diagnosing and treating TB. Having HIV predisposes children to contract TB, with severe side effects and a high mortality rate. We will never be successful in our mission of ending HIV/AIDS in children if we don’t address co-infection with TB. As a global implementing partner focused on pediatric health, we know at EGPAF that you can’t address one endemic disease that disproportionately affects parts of our society without looking at the other diseases that also put these very same people at risk.

Q: Progress in ending childhood TB globally remains remarkably slow. I wonder if you could tell us about some of the inequities and challenges that children face in this epidemic?

A: When we look at children and TB, it’s a crisis situation. Less than 50% of the cases are reported. So that means that we’re not even finding half of the children who are infected with TB, which leads to about 250,000 children a year dying of the disease. Of those, more than 52,000 are HIV-TB co-infected children.

The predominant reason we’re not finding the children who have TB is that diagnosing this infection in children can be difficult. Children are at a much higher risk of developing active TB especially when their immune systems are compromised by malnutrition or HIV or other diseases, which exacerbates the severity of the disease.

Diagnosing, and treating TB in children is fraught with challenges. The majority of the tests and treatments have been developed to address TB in adults and are not well suited for children. In the past couple of years, there’s been a lot more research and development into alternative types of samples that are easier to collect from children so that we can now begin to improve pediatric TB diagnosis.

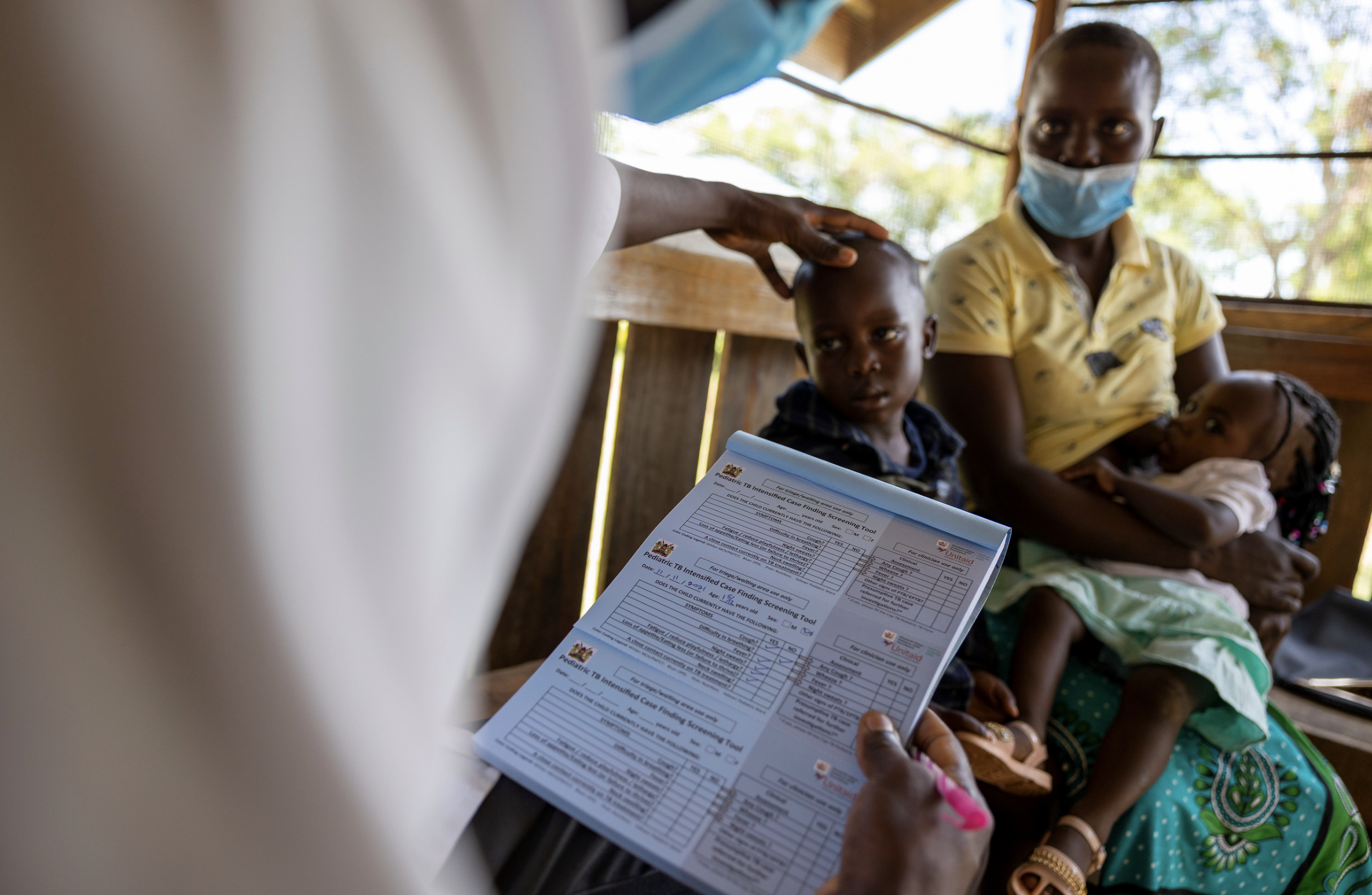

We tried to address some of these barriers through our Unitaid-funded CaP TB project. We assessed different interventions aimed at improving our ability to find children that have TB through contact tracing. When a person has been positively identified as being infected with TB, you start to test the people around them. We ask about their caregivers, the other people in the household. If children are in close contact with people who have been identified as having TB we are not able to provide them with child-friendly TB preventative therapy. These medicines will help to ensure they don’t develop active TB while living with others who are actively undergoing treatment for TB, very similar to how we address HIV using PrEP.

Contact tracing and TB preventative therapy are intensive methods for finding more children at risk of TB infection, but we feel that these are hugely important initiatives needed to close the gap for children and allow us to start to address this disease in this highly vulnerable population.

Q: What can we do to make sure that the tools that are most promising in testing and treating pediatric TB are accessible in the countries that have the highest TB burden?

We’ve been trying to catalyze the introduction of those new technologies and new treatments through our CaP TB Project. For example, there’s a dispersible fixed-dose combination for drug-sensitive TB. They’re dispersible in water, so the medicines are a lot more palatable, a lot easier for children to take. This new pediatric-friendly formulation then relieves the burden on the health care system and on the family members who are providing the care and the treatment every day by supporting easier administration and tolerability. These changes in treatments help to ensure that children complete their treatment which is critical to ensuring they are able to recover from the disease.

There are also new drug regimens that have become available that shorten the course of treatment down to three months. This shorter treatment cycle is critical to support children and families in completing their treatment cycles and supporting them towards full recovery. These regimens were recently approved by the World Health Organization, and are in the early stages of introduction into countries where TB is a significant health burden.

EGPAF plays a critical role in making sure that our country programs—and also the ministries of health in the countries where we work—are aware of these tools and that these new treatments are available. We have a responsibility to ensure that they’re made available on the scale that’s needed to be able to ensure that children are accessing these innovations on a routine basis and that diagnosis and treatment for TB are fully integrated into the health systems that support children.

Q: What can you tell us about policy gaps that can help move progress on childhood TB over the next two to three years?

A: We need to advocate for stronger political leadership, and accountability so that governments and ministries of health are able to quantify the amount of TB disease in their country so that we have a better global view to the burden. Without having good visibility of what’s happening on the ground in a particular country, it’s difficult to hold people accountable, and it’s difficult to have strong political leadership.

The pediatric agenda must become much more visible. We need to advocate for children to have access to health care, to be rapidly diagnosed and treated using tools that have been optimized for children. Countries need to prioritize the scale-up of new technologies, new diagnostic platforms, and new sample types that are designed and validated for use with children.

Q: We’ve seen the rapid development of several vaccines to address COVID-19. But the vaccine technology on TB goes back 100 years. And I’m wondering what barriers are preventing greater progress on a more effective TB vaccine?

Fundamentally it comes down to two or three different areas. One is that TB is a disease of the marginalized. It’s a disease of poverty. Motivating high-income countries to put the appropriate level of focus and attention on TB has always been a struggle.

The other part of the issue is that, unlike COVID-19, TB is a bacterial disease. The biology of producing an effective vaccine against TB has proven to be extremely challenging, similar to HIV—but for totally different reasons. This is where the political will and accountability—and funding cycles—are critical to be able to keep the pressure on and to keep supporting the groups that have been doing work for 100-plus years to continue working on improved diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines against TB.

It’s very easy to get distracted from the fact that this is a marathon race that we’re running against TB. It’s not a short sprint and, unfortunately, it’s a difficult one. But we need to maintain the focus and the pressure to keep that work going.

Dr. Sheila Tamara Shawa

Q: Adequate political and financial support to end childhood TB is critical to move faster towards the global targets. How is the African Union (AU) mobilizing the political will and resources to address childhood TB challenges?

Q: Adequate political and financial support to end childhood TB is critical to move faster towards the global targets. How is the African Union (AU) mobilizing the political will and resources to address childhood TB challenges?

A: The African Union has been at the forefront of building political will which is why an advocacy and accountability vehicle – AIDS Watch Africa – was established in 2001 following a special summit of African Heads of States and Governments to address the challenges of HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, Malaria and other related infectious diseases. In order to translate the political will into actionable steps to address TB, the AU develops decisions and frameworks to provide continental guidance on the control of TB. Key among these is the Catalytic Framework to end AIDS, TB and eliminate Malaria in Africa by 2030, the Africa Health Strategy, and our theme document: the Agenda 2063 “the Africa We Want”. Recently, the continent adopted the Common African Position on TB (CAP-TB), a document that further underscores the political commitment to address TB, and this is supported by the Africa TB Scorecard and the Continental Accountability framework. These documents have also embedded the need to address childhood TB as part of the overall program. However, because these processes require resources, having frameworks in place does not guarantee the implementation of agreed-upon objectives.

Generally, we have made great strides in addressing TB prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, because children are a special category of individuals, there is a need to develop specific strategies for the control of childhood TB. The AU has advocated for countries to come up with specific strategies that address childhood TB rather than embed the activities in the main TB control program. There is a need for specialized tools for the diagnostic and treatment of childhood TB in this regard. The AU also called upon various stakeholders to support member states at national levels through the provision of technical guidance and resources that can address the challenge of childhood TB.

Q: How do we make sure that governments and donors invest and support measures to increase accessibility to pediatric TB services?

A: One of the ways is to promote the alignment of national TB action plans to the continental frameworks as these provide overall guidance to address pediatric TB. With the support of donor investment, this objective can be attained if there is harmonization across the various players. Another way is to ensure that donor funding is aligned to national priorities as this ensures coordination of interventions for sustainable impact. It is worth noting that the AU has seen an increase in financing to TB programs in the last couple of years at national levels. This could be attributed to the inclusion of an indicator in the TB Score card requesting Member States to estimate the funds allocated to the TB program as more than two-thirds of the countries are now capturing data on domestic TB expenditure. Although data from the scorecard shows that the proportion of TB expenditure that was funded domestically in 2019 varied widely; ranging from 0% to 87%, this information provides some highlight on domestic investments in TB at the national level. Once all countries are able to capture the data on the domestically allocated resources to TB, there will be a need to disaggregate this further so that there is clarity on what is allocated to pediatric TB. Reporting on specific allocation to the intervention will help in addressing some of the challenges being faced.

Q: While we know that COVID-19 is negatively impacting global HIV services; how is the pandemic affecting the fight against pediatric TB?

A: The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the provision and access to essential TB services including diagnostics and treatment. We have seen a rise in the incidence and mortality rates (WHO report 2020) as a result of a lack of access to services. There has also been a reduction in the number of people that visited the health facilities for diagnosis and treatment due to lockdowns. Additionally, some of the equipment used to diagnose TB was re-purposed to help with the response to the pandemic. Health workers were reassigned to support the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Most importantly, funding, especially for TB, was diverted to address the pandemic both at the national level and from stakeholders and donors. As data regarding childhood TB is not segregated, these challenges affected the fight against pediatric TB in children as well as adults. With the COVID-19 pandemic disrupting much of the hard-won gains in the response to childhood TB, the AU is taking steps towards re-stabilizing health services to reach more children across the continent.

About Cassandra Kelly Cirino

Dr. Cassandra Kelly-Cirino has over a decade of experience as a senior executive in non-profit, research, private, and public health settings globally, and is a recognized diagnostics expert across multiple diseases areas spanning research and development, evaluation, validation, implementation, market access, and regulatory aspects. She began her career at the Canadian National Microbiology Laboratory focused on emerging infections, then spent a decade at the Wadsworth Center in Albany, New York as Deputy Director of the Biodefense Laboratory, followed by a 5-year period as Vice President, Infectious Diseases for DNA Genotek/OraSure Technologies. Most recently, Dr. Kelly-Cirino led a newly formed team at the Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics (FIND) as Director of Emerging Threats focused on the development of innovative diagnostic technologies to support countries in Africa and South East Asia to detect and respond to emerging infections endemic in their regions. In her role as Senior Director for Innovation and New Technology at the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation (EGPAF), Dr. Kelly- Cirino oversees EGPAF’s innovation portfolio including introduction of new treatments, models of care and diagnostics across EGPAF’s vast implementation platform. Dr. Kelly-Cirino holds a Ph.D. in Immunology and Infectious Disease from the State University of New York, Albany.

About Dr. Sheila Tamara Shawa

Sheila Tamara Shawa (Ph.D.) is a Senior Program Officer at the Africa Union Commission under Health Systems, Diseases and Nutrition in the Directorate of Health and Humanitarian Affairs (HHS). She is the focal person for TB, NTDs and the CHWs workers initiative. Dr Shawa possesses expertise in diseases control programs with over 10 years extensive experience in public health policy formulation and integration of efforts to promote preparedness to epidemics as well as address other public health concerns.

Dr Shawa holds a PhD from the University of Zambia in collaboration with the University of Copenhagen and an MSc in Infectious Diseases from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and a BSc from the University of Zambia.